Building better levees, tracking storms more accurately and training future emergency management professionals can have a major impact on community resilience to natural hazards. On the individual level, however, changing the behavior of residents in storm-susceptible communities could yield similarly fruitful results. When individuals get specific information about how a storm could impact their property and livelihood, these behavior changes could be even greater.

Dr. James Opaluch, a professor of Environmental and Natural Resource Economics at the University of Rhode Island (URI), leads a Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence (CRC) project that focuses on how individuals react to risk information. Dr. Opaluch’s project, “Overcoming Barriers to Motivate Community Action to Enhance Resilience,” aims to improve the resiliency of communities by providing better information on the barriers people face to adapting to coastal storm hazards.

URI investigators on the project include Dr. Austin Becker, Assistant Professor of Coastal Planning, Policy, and Design; and Donald Robadue and Pamela Rubinoff of URI’s Coastal Resources Center.

Addressing the ‘adaptation gap’

The project is based on the idea that individuals don’t react adequately to coastal storm threats for several reasons. Those reasons, Dr. Opaluch said, differ based on the type of decision needed, prior experience with similar hazards and characteristics of community decision-makers. These decision-makers can be people at all levels, from individual homeowners, to business owners, community leaders, to state and federal agenct employees.

To date there is little quantitative information on the ability of communities to adapt to the threat of coastal hazards.

“We’re all aware that there are many actions people can take – on the individual, community level, businesses, organizations – but many of those actions aren’t taken frequently,” Dr. Opaluch said. “We’re trying to understand what the barriers are that stop people from taking action – is it information, funding, the overall cost of a project – and how can we overcome those barriers?”

Decision-makers are often slow to adopt actions that will protect themselves, Dr. Opaluch said. This is called the “adaptation gap,” and the project focuses on better understanding the barriers that prevent adaptation and resilience.

Researchers will design and test interventions that can potentially overcome these barriers. Building resilience requires understanding the resistance of the community to adopting new behaviors, to identify barriers to adoption of hazard-mitigating strategies, and to design effective policy interventions to overcome barriers for different groups of individuals, businesses and communities.

Interventions to increase adoption rates include information tools to deepen the understanding of causes and consequences; improved information on specific, feasible protective actions; economic incentives for actions; and new policies or changes in existing policies.

Adopting insights from social science models of behavior change, researchers develop programs to improve the adoption rates of actions that can reduce potential damages from major coastal storms. Prior social science research shows that simply providing information is not generally sufficient to bring about changes in behavior.

Simulating effects of policy

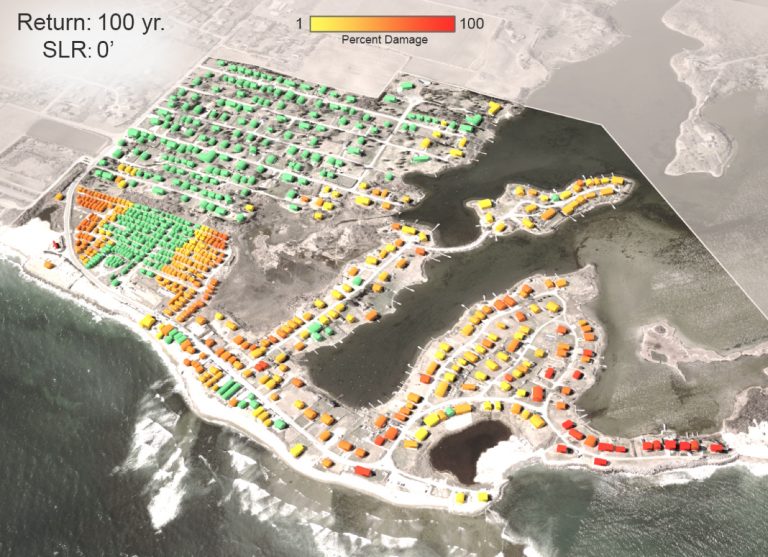

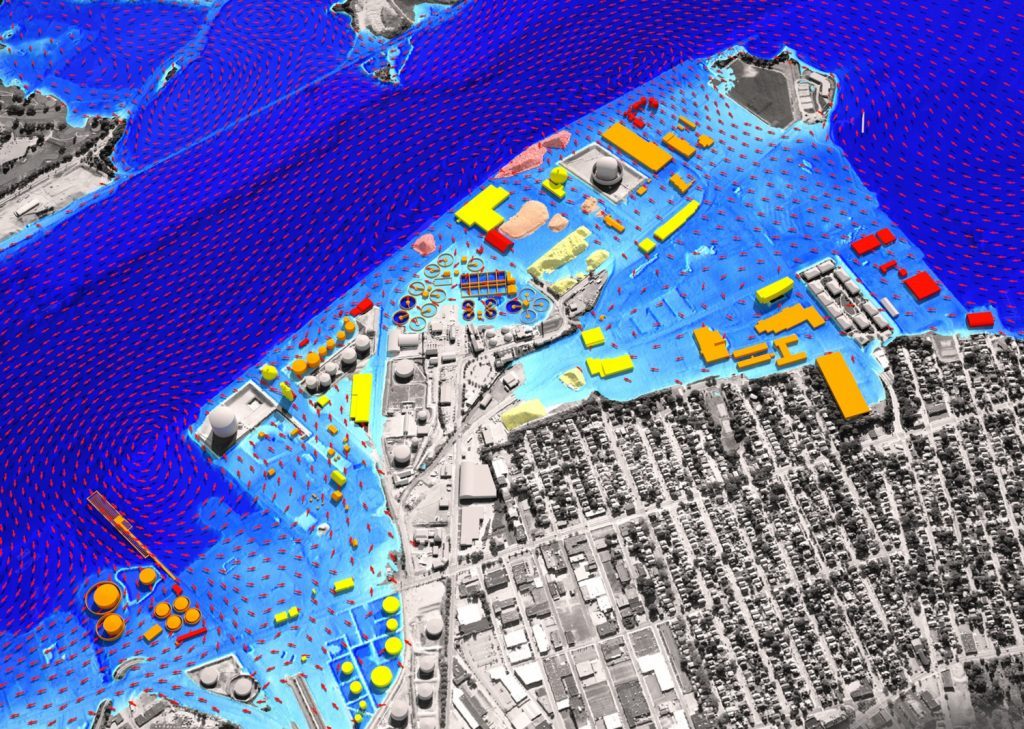

Researchers have found from earlier meetings that people living in storm hazard zones often don’t feel the storm threat is “real” enough, considering it theoretical. To counter this type of response, Dr. Opaluch and researchers will try a new method to get decision-makers invested in protecting their communities: Showing them exactly how a storm can impact their property. Researchers are using a policy simulation tool that creates visualizations of storm impacts using three-dimensional modeling, dubbed “Storm Tools,” combined with visuals depicting likely damages to structures. Work is expected to begin with focus groups and a pilot study later this year.

These planning tools were created as part of the Rhode Island Shoreline Special Area Management Plan, led by the State of Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council. The plan is aimed at helping individuals, businesses and communities prepare for sea-level rise and coastal storms. The data-driven visualizations use storm surge, wind, wave and debris flow information for specific infrastructure to provide economic and environmental impacts estimates. These estimates are applied to 3-D mapping of existing buildings in a community.

This tool will being applied to three case studies in Rhode Island: The Port of Providence, City of Newport and Misquamicut State Beach. The disaster visualizations, created by Dr. Becker and Dr. Peter Stempel, help decision-makers better understand the consequences of storms and the actions they could take to minimize damage. Policy simulation exercises help test the effectiveness of a range of protective actions. Researchers hope to be able to connect local hydrodynamic modeling and other simulations with the visualization tool. They ultimately hope to learn how such visual tools help reduce risk among local and non-local stakeholders.

“The period immediately after a storm is a good opportunity to rebuild to be stronger, but it is definitely not the right time to start planning. Plans must already be in place well before the storm strikes.”

In the aftermath of a destructive storm, Dr. Opaluch said, there is a “rush to rebuild,” and to restore a sense of normalcy. This period immediately after a storm can actually present an opportunity to better inform impacted individuals how they can be more resilient to future events.

“People want to get their lives back to normal as quickly as possible, so we often miss this opportunity to develop thoughtfully, in order to become more resilient to future threats,” Dr. Opaluch said. “The period immediately after a storm is a good opportunity to rebuild to be stronger, but it is definitely not the right time to start planning. Plans must already be in place well before the storm strikes.”

Proposed interventions include storm vulnerability audits – similar to an energy audit, experts assess specific structure-specific storm threats and actions that can be taken to reduce vulnerability, ranked by cost and degree of protection provided. Other interventions include providing a recommended set of protective actions along with incentives for adopting them; expediting the permit process for rebuilding and repairs; use of special financing, low-interest loans, cost-sharing and insurance discounts for repairs; and building the cost of protective actions in mortgage costs.

Using feedback from meetings with about 30 stakeholders in the first year of the project, project researchers have developed a list of opportunities for greater resiliency, barriers to change and interventions that can help overcome those barriers.

Expected end users for the project span a long list of private sector associations, educational institutions and nonprofit groups. They include Rhode Island realtor, insurer and builder associations, waterfront companies and marine trade groups and public agencies such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Coast Guard and Rhode Island Emergency Management Agency.