Only half of single-family homes in FEMA-defined Special Flood Hazard Areas are estimated to have flood insurance. Outside of those zones, the rate is estimated at 1 percent. Only 4 percent of homeowners are expected to voluntarily retrofit their homes to be better prepared for wind damages under Florida’s current wind mitigation credit program.

Retrofitting and insurance are primary ways to manage coastal storm risks, but both are relatively under-utilized. A higher rate of both could lead to significant savings in areas frequently impacted by storms, if only governments and insurers could find ways to make people purchase better protections.

That is the issue being studied through a Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence project led by University of Delaware professor Dr. Rachel Davidson. Researchers involved in “An Interdisciplinary Approach to Household Strengthening and Insurance Decisions” are attempting to understand the processes that lead homeowners to purchase insurance or decide to retrofit their homes to defend against natural hazards. These decisions, researchers say, play into a large-scale effort to manage existing building stock at risk from coastal storms. Other researchers on the project are Dr. Jamie Kruse of East Carolina University, Dr. Linda Nozick of Cornell University and Dr. Joseph Trainor of the University of Delaware.

“Insurance and retrofitting of homes are two of the ways we can make communities safer and protect existing buildings,” Dr. Davidson said. “We need to understand how people make decisions to do those things or not.”

Dr. Davidson and the project team are using phone survey data they previously collected about homeowners’ self-reported past and future hurricane retrofit and insurance decisions. They will use it to fit new statistical models of homeowner decision-making, and will integrate those into an existing mathematical framework they developed as part of an earlier project.

“Future programs and policies intended to reduce coastal natural disaster risk will be more effective if designed to align with how homeowners actually make these choices,” Dr. Davidson said.

Making communities safer

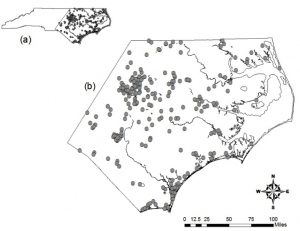

The survey data come from more than 350 homeowners in eastern North Carolina. The mathematical framework includes models of homeowner and primary insurer decisions, together with a model that estimates hurricane losses and inputs representing reinsurer and government roles. Using the model, researchers will fit choices made (buying insurance or not buying it, retrofitting or not) to the description of homeowner, type of home and alternatives available to them.

The research team will study the effectiveness of different types of incentives on, for example, deciding to retrofit a property.

“We’re trying to predict what percentage of people would undertake these tasks, to get a better idea of what the likely penetration rate is for insurance if we change the price or any of the characteristics of the policy,” Dr. Davidson said.

They hope the resulting models can be used to predict the percentage of homeowners in a region will buy insurance or choose to retrofit a property under each described circumstance or hypothetical, government-led program.

End users for the project include the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration – Risk Analysis Division; the National Preparedness Directorate in FEMA’s Individual and Community Preparedness Division; the Association of State Floodplain Managers; and the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Applied Economics Office Community Resilience Group and Materials and Structural Systems Division.

Developing a win-win

The project framework will capitalize on the emerging view that mitigation efforts are good investments that can save money before a disaster, as compared to costs for recovering from a disaster. Similarly, the whole community’s involvement broadens the impacts of decisions across a wider group of people than just the homeowners themselves.

So far, findings are that, as expected, higher premiums correspond with a lower percentage of homeowners buying insurance for flood damages. The trend is similar to that for wind damage. Demand for insurance, however, is not very sensitive to premium and deductible costs. Homeowners are more likely to purchase insurance if they have had a more recent experience with a hurricane or tropical storm, are in a floodplain, are closer to the coast, are younger and/or have a higher income. The recent experience factor had more of an impact when the storm caused damage to their home.

“Insurers, or in the case of the federal government, the National Flood Insurance Program, need to understand how to set rates,” Dr. Davidson said. “They need them to be high enough they can stay solvent in the case of an event, but also low enough that people will actually buy the products.”

For retrofitting decision-making, initial data suggests that grants to homeowners have a bigger impact than low-interest loans or insurance premium reductions. Homeowners that are closer to the coast, in a floodplain, in a newer home or have experienced a hurricane or tropical storm in the last year are, similar to the insurance purchase model, more likely to invest in retrofitting.

“We hope to put it all together to understand how we should be designing these policies so they are as effective as possible. We want to make sure that, from each group’s perspective, they are better off and more resilient at the end.”

Each of the end users in this project face challenges. Homeowners who do not have appropriate insurance and have not retrofitted their homes face longer roads to recovery after an event. Governments, similarly, face larger, unexpected costs that can disrupt the efficiency of municipal budgeting. Insurers have to price insurance low enough that it is purchased but high enough to insure profits and fiscal solvency.

A “win-win” tool or approach that addresses these interdependent needs and challenges would depend on homeowner biases that include aversion to upfront costs, underestimation of the probability of a disaster and a short time in which to make changes, Dr. Davidson said. Ultimately, the researchers plan to develop a software tool to help state-level officials identify and evaluate alternative public policies aimed at finding effective, sustainable, win-win solutions to better manage natural disaster risk associated with existing buildings.

Specific policy tools could range from offering grants up to a certain percentage of homeowner retrofitting costs, at a capped amount. Alternately, it could include a program to buy damaged homes up to a percentage of their market value. The tool could help agencies think about the role each end user group can play and how different policy choice could impact each group.

“We hope to put it all together to understand how we should be designing these policies so they are as effective as possible,” Dr. Davidson said. “We want to make sure that, from each group’s perspective, they are better off and more resilient at the end.”